Will you be alright?

Will you be alright? some of our friends asked when we said we were moving into new-build on a ‘development’. Some of this fretting I suspect was born out of genuine concern for our creative souls. Would we shrivel artistically and creatively amid the homogeneity of the ‘carefully curated collection of 2,3,4 and five bedroom homes’ that would be our new neighbourhood. It’s not really you, is it? suggested one of our first visitors on arrival.

Look, we know it’s not really us. As in, we’ve always lived in older houses (three Victorian properties over a forty year period for the record) in established – is that the word? – neighbourhoods. I liked the atmosphere of each of these homes, the patina of polished floorboards and old brickwork, the fireplaces, the high ceilings – all of that. Being in the town centre in our last house – walkable to the library and arts centre, independent bookshop and almost comical number of artisanal bakeries and coffee shops – was another upside. And, of course, there’s social cachet attached to certain types of houses and neighbourhoods (and not to others).

Anyway, here we are in our neat new-build in what you might call the Vernacular Lite style (where national house builders give a nod to local building styles – in our case we get red-black clay tile cladding, some pointy micro gables and an entirely cosmetic chimney). If I have a personal gripe about new building developments it’s this deference to traditional or local building styles. Because as much as people decry ‘modern’ housing developments, only a tiny percentage of new housing is modern in any confidently modernist sense. House builders aren’t entirely to blame for this. They need to get project approval from local planning authorities whose housing policies require developments to be ‘harmonious with their surroundings’ and to demonstrate ‘contextual sensitivity’. These attributes seem to be unquestioningly equated by LPAs with ‘well designed’, another essential compliance requirement – and so, Vernacular Lite becomes the frictionless default.

Otherwise, our new house – and the way the space flows (to get a bit Kevin McCloud about it) – is working well for us. We are enjoying the novelty of winter warmth (with a predicted halving of our energy bills) and of living somewhere where everything works and functions as a discernible whole, with a kind of internal logic.

But will these new home comforts, these perfect white walls and mandatory beige carpets throughout, create conditions unconducive to creative thought and activity? This has certainly crossed my mind. And as I sit here in near silence on a grey Sunday morning in late February, there is a palpable sense of being insulated – literally (by the half metre deep Rockwool in the loft space) and metaphorically – from the outside world. If my spartan office/studio fails to ignite the spark, will the garage – where a drawing table, paints and brushes nestle among strimmers, hedge trimmers, spades and forks – produce more utilitarian, purposeful vibes? In short, will I be alright in my ‘new chapter home’?

Choosing my words

Words have been raw material all my professional life as a journalist and editor. The role of journalist-as-gatekeeper of information – ‘news’ – has changed in recent years to become more information verifier, navigating the cacophony of unmediated digital noise. The word-based work I have made over the years is in response to this forced engagement with messaging – from the fairly anodyne (product press releases, say) to the weaponised vocabularies used to intimidate and attack individuals and capture policy – and all points in between.

The earliest of these projects explores the psychology of public health messaging, specifically on-pack tobacco warnings. When I started producing my own versions of the messages the official warning on cigarette packs was the undeniably to the point ‘Smoking Kills’. But it had taken a couple of decades for that level of explicitness to be reached (starting out with ‘Smoking Can Damage your Health and progressing through ‘Tobacco Seriously Damages Health’ and increasingly blunter variants. Supplementary messages must also be featured prominently, among which ‘Smoking Can Cause a Slow and Painful Death’ has a certain standout quality. But my guess was that, as with everything over-familiar, these words quickly fail to register and blur into a word pattern. It made me wonder what kind of messaging might really pull people up. Genuinely unsettle them. Maybe I could harness some Old Testament-style fear factor (God Have Mercy on Your Soul being one example), or dark comedy (Die You Bastard, Die). I photographed the crumpled/discarded packs in settings where they would typically be encountered. I originally planned to leave the packs in situ for 24 hours to give them chance of an artistic afterlife; the potential to be ‘discovered’, re-presented on social media. But guessing that they would more than likely be picked up by already troubled individuals, I resisted. I am a conceptual artist with a conscience.

On a supplementary note, I’m in the middle of reading Street-Level Superstar: A Year With Lawrence, Will Hodgkinson’s brilliant evocation of the tragicomic life of the criminally neglected pop genius Lawrence Hayward (who must be known only as Lawrence). Lawrence’s foibles are multiple but one in particular stood out – his habit of decanting the contents of a new pack of cigarettes into a beloved old pack “featuring his favourite tobacco warning” (a luridly coloured photo of rotten teeth).

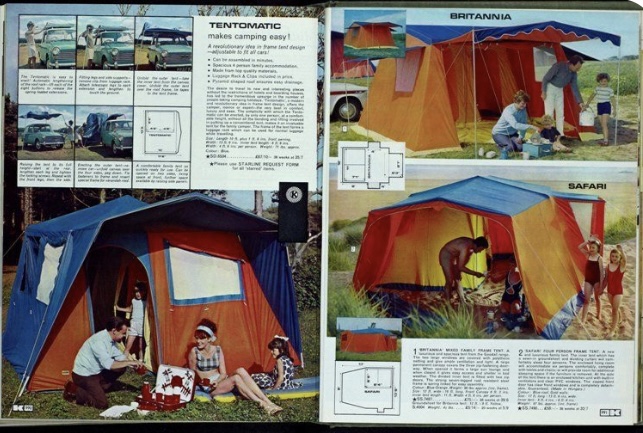

THE TRIUMPH AND TRAGEDY OF THE TEnTOMATIC

One afternoon in the summer of 1971 my Dad returned home from work in an unusually triumphant mood. He had secured, at a spectacular discount he told us, a device which a man at the Crystal Palace Tent and Caravan Centre assured him represented the “future of camping”.

In retrospect I’m surprised that Dad, ‘in sales’ himself, didn’t suspect there might have been a reason for the whopping 50% off he’d been given, without negotiation, on the Tentomatic (yes, really)*. Getting shot of the remaining stock of Tentomatics as quickly as possible, for example.

The Tentomatic had been purchased a couple of weeks ahead of our first ‘foreign holiday’, as we enthusiastically described it. We’d had dry run at camping earlier in the year, in Dorset, in a borrowed tent. But now we needed to demonstrate commitment by acquiring the full camping kit and caboodle, with a brand new tent as its centrepiece. Around the same time my mum began amassing startling quantities of convenience food (Vesta curries, chunky chicken, Cadbury’s Smash and canned butter come to mind) for our fortnight in south west France, clearly a grocery-impoverished wasteland in her imagination.

Looking back I now see the canned butter (developed initially for military and expeditionary use) and the Tentomatic as analogous. Both offered a promise of technological advance, both were vulnerable to human shortcomings. Butter we learnt, canned or otherwise, turns into an unusable yellow liquid in the sauna-like conditions of a zipped up tent in mid-summer. But at least this discovery was made in private. The debacle of the Tentomatic was a horribly public affair.

The idea of the Tentomatic was that the whole thing was packed into a proprietary roof-rack device mounted on the top of a car, forming the tent’s roof frame. You would arrive at your campsite pitch, park your car and then releases a series of catches from which the tent frame legs would shoot out to be snapped into place. With the tent frame now effortlessly assembled, you simply drove your car forward and rolled down the tent canvas (still in-situ in the roof-rack) to be pegged down.

When we arrived at our first campsite in France, a wooded idyll in the Loire Valley, I was acutely conscious that we were simultaneously torch bearers for the future of camping and total camping amateurs. And as we drove up to our pitch I surveyed the scene around us from the back seats of our Ford Cortina estate with growing discomfort. It was lunchtime. Families sat languidly around camping tables that bristled with baguettes, unseen-before cheeses, cold meats, salad and half-empty wine bottles.

We parked and got out of the car. Dad began releasing the tent leg catches, snapping them down with, I had to admit, impressive efficiency. Very quickly the general insouciance that greeted us on arrival was replaced by intense curiosity directed at the futuristic contraption being erected around our Cortina. I heard ‘l’Anglais’ muttered a few times by the intimidating group of campers now gathered around us.

Unfortunately what should have been a moment of triumph – the Cortina being driven forward to leave behind a fully erected Tentomatic – ended in humiliation as the car and the Tentomatic juddered forward in unison, before the latter collapsed on itself after finally breaking free from the Cortina. At this point the crowd dispersed and we were mercifully ignored as we repacked the tent and started the procedure all over again.

Before setting this out in print I Googled Tentomatic just be sure the thing actually existed and wasn’t a joke name made up by dad to embellish the many apocryphal retellings of the above saga. Straight away there it was, exactly as I remembered it. Apparently it had been available in two variants, the Britannia and the Safari. We had the Britannia, with its desirable vestibule area (the site of another calamity involving an imploding unfilled kettle and high velocity redistribution of our baked beans and cocktail sausage tea).

Seeing the Tentomatic again has brought memories flooding back, including memories of actual flooding (one of waking at 5am to find dad frantically digging gullies around the Tentomatic as an apocalyptic sky began to empty biblical quantities of rain down on us).

You’d think these travesties might have dented our enthusiasm for camping. But I think we just accepted that camping was essentially a constant test of fortitude (not to mention theatre of embarrassments). We must have done because my parents persisted with camping – at the exclusion of all other holidaying possibilities – for pretty much the remainder of the decade.

* This is made all the more baffling by the fact that two of my dad’s favourite words in the English language were ‘bullshit’ and ‘kidology’.

THE BEQUEST

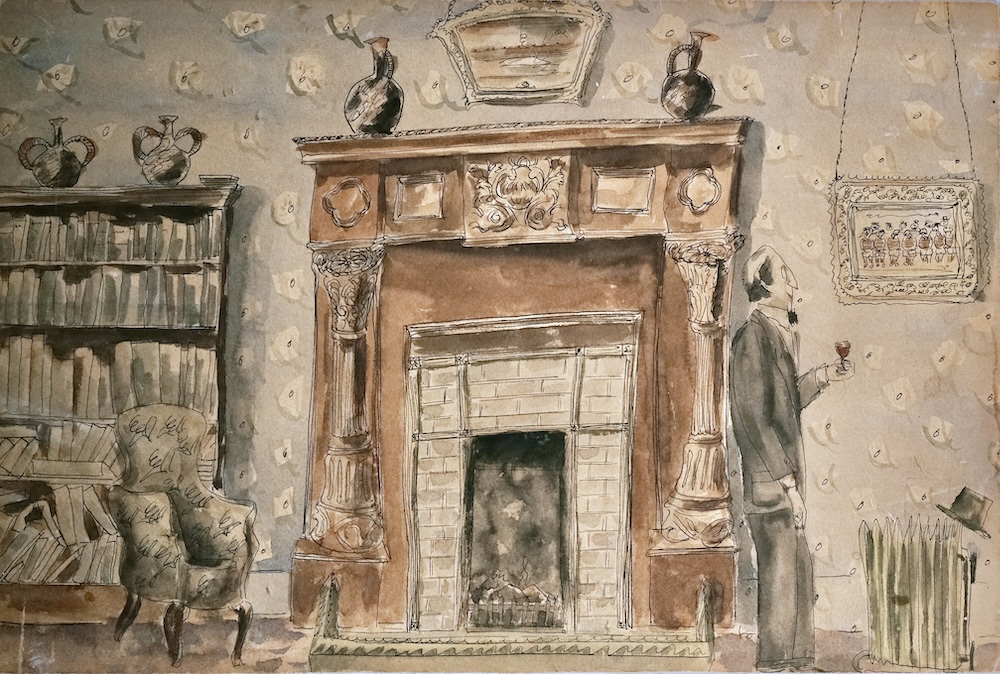

“Pen and watercolour done by Mike Manson. It is of the fireplace, bookcase and chairs in a room at, Palace Road, E. Mosley, Surrey. Painted when I was at school, aged 17 in 1949.”

The inscription, in my Dad’s unfailingly breezy hand, is in red biro on the plywood offcut to which the painting has been glued (almost certainly with Cow Gum, his glue of choice for decades).

I’ve just recovered this painting from under our bed. I’m slightly ashamed that this has been its unglamorous resting place for the last few years, especially since Dad formally bequeathed it to me (a declaration also made on the plywood mount in biro). The bequest, dated 2011, wasn’t made because he anticipated his imminent demise but because I’d been admiring it one day when we’d been over for Sunday lunch.

Dad’s painting is of the rambling Victorian house that the Manson family (never looks good in print) and assorted Gadds rented during the 1950s. The Palace quite reasonably referred to in the road name is Hampton Court, situated just across the way. Dad notes that both the Claret-clutching gent in the dinner suit and the top hat jauntily resting on the radiator are fictional elements in the composition. The room and furniture are faithfully captured as they were, he says (family photos from the period testify to this).

Dad was naturally talented at art and this was already being recognised at school. He chose a book of Saul Steinberg’s drawings when he was awarded Surbiton Grammar School’s art prize, and I think I can see a Steinbergian influence in the Palace Road drawing. A little later he was offered a place at The Slade, then as now ranked as one Britain’s top art schools. But he deferred, deciding he would first get his National Service out of the way. In the end, life – marriage, the arrival of yours truly, a job offer with Daisy Fresh Cakes and the prospect of a mortgage – took precedent over art and he never took up his place at The Slade.

I don’t think Dad was much of a ‘what if?’ type of person. But I did notice that whenever he met someone with an art background he would mention his place at the Slade. And when, in the late 1970s, I was accepted onto the fine art degree course at Bath Academy of Art he was proud in a way I’d never seen before.

Dad died in 2014. Nearly a decade later we were clearing the house that he and mum had lived in four forty years, sorting through possessions and keepsakes acquired over eight decades (including a tin of Cow Gum still apparently in active service). On the last day, when we thought we were done, Liz asked me to feel along the top shelf of a large cupboard in what had served as a stock room for the souvenir business he and mum ran from home, sensing that something was still there. There was something. I took down a tiny, faded blue portfolio. It contained the selection of drawings and paintings that Dad had submitted to The Slade. Two things immediately struck me about the work: the way it was so utterly fixed in time stylistically (the Ardizzone-like flourishes of the pen and wash drawings) and subject-wise (the very 1950s wardrobe of the schoolboy sitter in the still lifes); and the maturity of the observational work (several confident life studies and a beautifully delicate botanical watercolour). I know this was Dad’s Slade submission because he inserted a note explaining this was the case – naturally seizing the opportunity to re-tell the story about the place he had subsequently been offered.

The work in the small blue folder, though artistically inchoate, is alive with potential. And perhaps that’s why I felt a sharp sting of poignancy when I unknotted the little portfolio ribbon to bring Dad’s drawings and paintings back into the light of day for the first time in nearly 70 years.

Honest drips and the limited value of Howard Hodgkin

“I think there are limits to what you will be able to learn from looking at Howard Hodgkin,” the painter Peter Kinley once said to me in a slightly oblique aside.

We were talking in my studio space at Bath Academy of Art (BAA) where I was a student in the late 1970s. Peter didn’t teach in any conventional sense. He would appear in my space and begin a conversation about the work I had been making, which would then tangentially re-route to any of the topics currently occupying his thoughts. The conversation would often end as abruptly as it began, or return to its starting point. On one visit, as he was about to leave, he hesitated at the door before turning back to tell me: “If you are going to make a feature of the drips in your paintings I’d be inclined to accept where they go, where they travel – not try to contrive how they look. Just a thought.” I have avoided contrived drips and obviously authorial mark-making generally ever since.

I’m sure there was context to Peter’s comment about Hodgkin (a former tutor at BAA himsel and occasional visiting speaker), but I can’t remember it. It could easily have been interpreted as professional envy since Hodgkin at the time was enjoying spectacular critical (“the greatest English colourist since Turner”) and commercial success. But it wasn’t at all. The two of them were close friends, apart from anything. I think it was more that Peter considered Hodgkin’s paintings a sealed world – elusive, elliptical. That they revealed little about the process of their making. Famously, though, Hodgkin talked about the process of making paintings often and at length. He was keen to the point of conscientiousness to emphasise that his paintings – seemingly made rapidly with broad, wet-loaded brushstrokes – typically took years to complete. In other words, what you were seeing in a Hodgkin painting was a kind of layering of artistic time, a temporal record.

I suspect that what Peter really was saying, was that Hodgkin can quite easily be imitated (and often is) but the result is likely to be just that, an imitation, an etiolated version of Hodgkin’s chromatically supercharged and deeply personal response to the world.

It’s official, i once sat on Phil Lynott’s leather jacket

On the 27th of October 1974 I sat on Phil Lynott’s jacket, a story solemnly corroborated recently on WhatsApp by three old school friends.

Strangely, while I have very clear memories of seeing Thin Lizzy play the Croydon Greyhound in 1974 and of the heart stopping moment when I first noticed Phil sitting at the table next to us in the bar (and of catching sight of the implausibly long and resplendently leather-clad legs protruding from under the said same table), I have no recollection whatsoever of making tantalising contact with Mr Lynott’s totemic leather jacket.

Perhaps my own memory was repressed to protect painfully self-conscious teenage me from permanent flashbacks of a humiliating exchange with the annointed Ace of Bass.

In the event, the interaction between Phil and me was somewhat scant, roughly along the lines:

Phil (Guinness in hand): “You alright there, lads? Can I just get my jacket back.”

Me: (Oh, God, I’m sitting on it) “Oh, sorry, yes”

Short, yes. But “nice and polite, mind,” as my friend Mark remembers.

4/24

Cycle of hate

Entirely unintentionally I have been conducting a small scale study into attitudes to cyclists and cycling. The findings, as I shall ambitiously call them, are striking.

There is a zebra crossing in Tunbridge Wells that I use regularly. More often than not I am fully pedestrian (the best description I can think of) when I approach it, on my way into town, or to visit my mum. But not infrequently I have my bicycle with me. Over a period of months I have noticed markedly different behaviours from motorists who encounter me waiting to cross at the zebra, depending on when whether I have my bike with me or not. I should stress here that I am not on the bike, it’s by my side ready to be wheeled across. As a bit of added detail, the bike in question is a non-threatening Brompton folder.

Empirically, I have discovered that drivers are about 25% less likely to stop to let me cross if I have my bike with me. I have wondered if there is confusion among drivers about the status of a pedestrian with a bike under the rules of the Highway Code. Do people think the presence of the bike disqualifies you from being a pedestrian? But my hunch is that what is being revealed is the level of disapproval of cycling/cyclists in the population at large. Ranging from mild aversion to out and out hatred.

The New York Times contributor Jody Rosen notes in his book Two Wheels Good that fear and loathing of cycling and cyclists goes back almost as long as bicycles have existed (just over 200 years). The bicycle, says Rosen, has always been a lighting rod, adding that “where the bicycle goes, controversy flares, and culture wars erupt”. As well as highlighting familiar contestations between motorists and cyclists over the right to road space and squabbles over transport priorities, Rosen shows us that something darker and more troubling is in play. There is a general prejudice that the “bike is by definition absurd and illegitimate”, and the view – famously articulated by PJ O’Rourke – that cyclists are “backward thinking atavists and an affront to progress”. More extreme prejudices against cyclists are likely to stem from the idea that cycling is something alien and ‘not right’. Rosen quotes from a 2019 Australian study into attitudes to cycling which suggests that in heavily car-based societies “on-road cyclists … look and act differently from typical humans”. The same study found that 49% of non-cyclists view cyclists as “less than fully human”.

Which is probably about as dark as I want to get here. As regards my own modest study, I probably have to concede that more research is needed

12/23

Re-reading kerouac. or not.

The other day in the coffee shop that adjoins our local library I noticed a man – probably in his late 70s – reading On the Road. I made the assumption that he was re-reading Kerouac, and wondered to what effect. Kerouac, it is sometimes said, is one those writers you read when you are young and you should leave well alone later in life.

When I was sorting through some of our old books recently I wondered what to do with my own copies of On the Road, Catcher in the Rye, The Alexandria Quartet and the rest. It wasn’t so much that I would never read them again, it was more that I wouldn’t be able to bear to read them again. This proved to be the case with Durrell. I got about as far as page 20 of the mesmerising and exhilarating (as I remembered it) Justine. Perhaps it’s just that the youthful sensibility that primes us for certain types of writers and writing – the books with ‘so much to say’, to use Geoff Dyer’s phrase – is just too long gone in this case.

But what if the coffee shop Kerouac reader was entirely new to On the Road? He’d simply picked it out at random from the library shelves, oblivious to its ‘defining work of the postwar Beat and Counterculture generations’ status. I thought about this as I watched him in a low lit corner of the café, carefully turning the crackling caramel-coloured pages, reading intently.

10/23

That’s really noT kafkaesque

‘Kafkaesque’ is word I use with quite obscene confidence to describe certain types of disorienting situations. Just like hordes of other people who have never read a word of Kafka.

Kafka biographer, Frederic R.Karl, argues that Kafkaesque has entered the language in a way that no other writer’s has. He gripes that it is misused on an industrial scale. He told the New York Times: “What I’m really against is someone going to catch a bus and finding that all the buses have stopped running and saying that’s Kafkaesque. That’s not.”

Point taken. But thus far I’ve not been openly challenged about my context-guided, dictionary definition-informed use of Kafkaesque. It’s just possible however that someone might inform me in the strongest possible terms that something or other “is absolutely not Kafkaesque”, which would, it’s true, be dignity shredding.

10/23

Accidentally Jean Rhys

As well as the more famous literary allusions, at a more domestic and personal level we might invoke some more minor ‘esques’ or ‘ians’ in moments of shared recognition. Without having to think very much about this, my wife and I both agreed we are especially attuned to any potential situation that you could call Accidentally Jean Rhys. This could be an atmosphere (a particular quality of melancholy, probably heavy with self-absorption), a Rhysian aesthetic. But it could also be the sighting of a solitary figure at a café table resembling a protagonist from Quartet or Good Morning Midnight (ideally the cafe would be in Montparnasse, the table zinc topped and she – almost certainly she – would be smoking Caporal cigarettes and drinking strong black coffees). The peak of our Jean Rhys reading took place when we lived in Upper Norwood in the mid 1980s, which was when we discovered that Jean had lived for a short period (unhappily and resentfully, naturally) just one street away from our own flat. This was serendipitous for us and presented the potential for yet more Rhysian moments (with Norwood’s grander boozers standing in for pavement cafés).

10/23

Sisters and ciggies

Here are my Scottish grandmother and great aunt. The photo is undated, but I’m guessing 1970s. They’re on a beach somewhere, sitting in the marram grass. It doesn’t look like the beaches of the Fife coast where we played as children. I think they’re probably holidaying ‘down south’ (although the beach wear is hardly suggestive of balmier climes). They both look utterly at ease in each other’s company. This is rather nice to see because my buttoned-up Nana and spectacularly gregarious Aunt Toosh could be prickly together. Here they look like besties. Sisters and ciggies.

10/23

career advice

(Winter 1979. I’m standing in the driving rain by a slip road onto the M4, hitching a lift to London. A van has pulled up)

“Where you going?”

“London.”

“You’re in luck, jump in. Trevor.

Was I in luck, I wondered as I climbed into Trevor’s van. A glance over my shoulder revealed this to be full to the roof with carpets of varying degrees of luridness. As we pulled onto the M4, I watched Leigh Delamare services in the side mirror recede into late afternoon murk.

“I’m in carpets,” Trevor shouted as we picked up speed. He told me he was on his way to a “big job in London”. And about all the different types of carpets he had on board – twist pile, cut and loop, tip sheared and the rest. He told me about the best type of underlay and what gripper rods were for. He said you had to have nerves of steel to run a Stanley knife down a 20 foot length of Axminster. The carpet trade was solid. There was good money to be made. “I’ve done alright for myself”.

“What do you do?” Trevor asked.

I told him I was an art student. Almost as soon as the words left my mouth I could sense this information had not registered well with Trevor.

A quarter of an hour or so passed. Trevor was looking straight ahead, intently. Thinking. Then he turned to me and shouted: “I’ll tell you what you want to do mate. You want to fuck art and get into carpets”.

Only the metronimic thwump of the wipers broke the now deafening silence. I could just make out a sign in the watery distance. London. 104 miles.

10/23

career advice 2

I’d been working as trainee journalist for a small publishing company in Croydon in the late 1970s for about 18 months, when my boss – a seen-it-all-before Fleet Street hack (his description) – decided to proffer some unsolicited career advice. This was probably at the end of yet another day of me rather obviously displaying my bitter resentfulness at being shackled by office life.

I looked up as the machine gun clatter of his two-fingered typing stopped abruptly. John put down his cigarette and composed himself. “Have you ever thought of applying a full-arsed approach to your job. It might be quite an interesting experiment”.

“Please take that in the spirit in which it was intended,” he added, before he resumed jabbing out his copy.

A more constructive adjunct followed a few minutes later . It went something along the lines of: ‘You’re in the office for 8 hours a day, so you might was well make something of that time’. However mundane this sounds, it turned out to be an attitude-shifting moment that I remain grateful for to this day.

10/23

warning

“If you carry on like this, you’ll end up in journalism,” my English teacher Mrs Adams said to me as she handed back my marked homework. Was this intended as a stricture, or an invitation to continue “like this”? I really had no idea. But either way it didn’t matter. I had already applied for a place at art school, and I was very definitely going to be an artist.

I have been a journalist for 45 years. Well spotted, Mrs Adams.

10/23

Dad, Billy and Dudie

Here is my dad (right) with his brother Billy and their mother (my grandmother, known to me as Dudie) in the mid 1940s. Two boys clearly very at ease about displaying their affection for their mum. This little tableau reminds me of a story my dad told me about how he and Billy had arrived home from school one day during the war to find their mum standing on the doorstep of their house with two packed suitcases. “I’m sick of this. We’re going to find dad.”

The boys’ dad (my grandfather, Robert Gair Manson) had mysteriously – as far as they were concerned (and probably as far as my grandmother was concerned too) – disappeared from the domestic scene. In fact, Robert, who served with the Royal Signals, had received a summons to report for work immediately at an operation run by the Secret Intelligence Service, providing the scantest possible information to my grandmother by way of explanation.

That afternoon, Dudie, dad and Billy took the train into London, then on deep into the Buckinghamshire countryside. My dad recalled stepping out of the train at a small country station. He made a point of remembering the station name. Bletchley. That evening my grandmother began knocking on doors of the houses in the town, enquiring about accommodation. A woman said she could take them in for a fortnight.

Robert, quiet, unassuming and utterly reliable, never spoke a word to anyone about his war service. After he died my dad found his summons papers (for his posting to Whaddon Hall, part of the Bletchley Park code-breaking operation).In the early 2000s Robert Gair Manson was added to the Bletchley Park Roll of Honour shortly after my dad presented Robert’s official papers and his own corroborating story.

10/23

the day my life didn’t change forever

On 25 June 1972 I didn’t see David Bowie at the Croydon Greyhound and my life didn’t change forever.

I was part of a small group from school who would go the Greyhound almost every Sunday to watch bands (we called them groups) play at the Fox’s club (tickets 75p in advance, £1 on the door). We were undiscriminating about who and what we saw. Folk, Prog, Glam, Rock – we were up for it all. So: Thin Lizzy one week, Gensis the next, Fairport Convention the week after. The only rule we applied was that one of us would have to have heard of the group playing.

So when the venue’s MC ambled onto the stage at the end of the previous Sunday’s show and announced to a few stragglers “er, next week it’s David Bowie” (cue, smattering of applause), we looked at each other and agreed that none of us had heard of him, and that we wouldn’t be going.

But within weeks we’d all heard of David Bowie. Starman was in the charts. Then John I’m Only Dancing and The Jean Genie. My friend Julian bought Hunky Dory and that summer we listened to it on repeat in his bedroom in a thick haze of joss stick smoke. From then on I bought just about every album Bowie released. Around the time Station To Station hit the shelves at Cloak’s Records in Croydon I was doing my art foundation course. I took my cue from the cover photography from that album when I went as Bowie to a student fancy dress party, hoping to radiate Thin White Duke vibes. In the late 1970s the mournful sonic landscapes of Low and Heroes, a sharp counterpoint to the angry urgency of punk, would form the soundtrack to my three years at Bath Academy of Art. A few seconds of any track on Let’s Dance transports me with startling vividness back to 1983, the year my wife and I met and married.

But years went by before any us of mentioned the Greyhound incident (or non-incident). We’d just got the beers in at a class reunion in the early 1980s, when my friend Mark said out of the blue: “Do you remember that time we didn’t go to see David Bowie?”. I think we just looked at each other and quickly changed the subject.

The true ghastliness of our decision didn’t really dawn on me until much later. Bowie obsessives and historic gig compilers on the internet helped me discover that in that summer of 1972 Bowie was previewing his just released Ziggy Stardust album – Moonage Daydream, Hang on to Yourself, Suffragette City and rest – and persona, and that these had been incendiary shows. Literally a life-changing moment for many who experienced them.

But our lives would trundle on unchanged.

Just to make the whole thing slightly more painful, I learnt recently (from Mark, who stumbled across the original gig ticket online) that the support act on 25 June 1972 was Roxy Music (full glam pomp Virgina Plain vintage).

10/23

You won’t have heard of us, we’re called Roxy Music

My old art school friend Rupert Fawcett went to Holland Park Comprehensive in the early 1970s. There was a hip, young music teacher there at the time who had let slip was in a group. The kids in Rupert’s class wanted to know which group Mr Mackay was in. “You lot won’t have heard of us, we’re called Roxy Music”, he told them, with total confidence. His friend, the pottery teacher, Mr Ferry, was also in the group.

10/23