Why did you have to go and do that, Phil?

It’s the late 1950s and the American artist Philip Guston is at the pinnacle of his abstract expressionist phase. He should be enjoying his major player status as part of the exulted New York School. But Guston is struggling to find meaning and purpose in abstraction. Torn between competing impulses – depicting the actuality of the world around him, or abstracting it – he is hit with a juddering realisation: “The hell with it, I just want to draw solid stuff”.

Guston was done with the loops and skeins, the diaphanous veilings of abstract expression. His abstract painting was boring him. To the extent that he stopped painting for an entire year. Then he began, slowly and deliberately, to draw his way back to painting. Over the following year, sparse arrangements of horizontal or vertical black lines and simple grids gradually morph into the heavy outlines of everyday objects – books, shoes, boxes, window frames. Figuration had come calling again.

Renouncing abstraction (Guston had decided that American abstract art was “a lie, a sham”) was one thing. But the way Guston effected it, as a kind of artistic handbrake turn, had instant reputational consequences. When he first showed the new work – including early versions of the ‘hoods’ (cartoonish paintings of Klu Klux Klan-like figures in unsettlingly banal situations) – at New York’s Marlborough Gallery, in 1970, the reaction was excoriating.

The provocative iconography of Guston’s figurative work has been the focus of most recent discussion about the artist. But in 1970, what Emma Sullivan has called Guston’s “violation of virtuosity”, caused just as much offence. Critics and artist friends alike were horrified at what they saw as the crudeness of Guston’s new cartoon-like idiom. As Guston recounted in an interview with Michael Blackwood: “They told me they hated the new work. One of them, and I don’t need to name names, said to me, ‘Phil, why did you have to go and do that?’.” Perplexed at Gaston’s apparently wilful embrace of ugliness John Cage could only say, “but you’re living in such a beautiful country”.

Several commentators have likened Guston’s dramatic return to figuration to Bob Dylan going electric at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. No one actually shouted “Judas” at Guston but purists in both spheres were riled in about equal measure.

In declaring himself “sick and tired of all that purity”, Guston was disassociating himself from what he saw as the introspective preoccupations of abstract expressionism. As Karen Schneider put it, “he felt that he could could no longer justify the luxury of adjusting a red to a blue in his abstract painting when the world was in turmoil”.

Artists falling out with artists is sometimes unavoidably funny. In the case of Guston’s bust up with the Abstract Expressionists, the comedy potential was in proportional relationship to the deadly seriousness of the endeavour. Guston had dared to challenge the heroic narrative of American Abstract Expressionism, cultivated so assiduously by artists, critics and gallerists alike. The bait was laid. The AbExers swallowed it whole.

Philip Guston is showing at Tate Modern until February 24.

2024

Along for the ride

Why am I just about the only person of my age that I know who rides a bicycle as transport? It’s a question I’ve been asking myself quite a bit lately (in my head, obviously).

In struggling to answer it, I want to make an analogy between cycling and drawing. Both are activities that we are encouraged to do when when we are very young. Drawing is regarded as central to early years development (builds fine motor skills, helps with communicating emotions and thoughts, develops pre-writing skills). Learning to ride a bicycle is also firmly categorised as a ‘good thing to do’ when we are young (improves fitness, helps focus and learning, is a fun way to get around). But encouragement levels for both activities rapidly evaporate as we get a few years older. Drawing is suddenly something that is compartmentalised in our lives, and typically confined to school art lessons (where they still exist). Bicycles languish in sheds as older children become self-conscious about public displays of physical activity. Or decide that cycling is too ‘young’. Or – I’m going to put out there – abnormal.

I rode a bike as a small child. But I stopped for a few years, I think from the age of about eight or nine. There was probably every chance that I would never take up cycling again. But a fortuitous turn of events ensured my return to the saddle. In November 1971 (I would have been 15) a close neighbour had just returned from working in the Netherlands for a couple of years. He’d bought himself a bike to get around on there, where cycling was entirely normalised as a form of adult transport. Back in Britain he couldn’t see himself using it. So he sold his beautiful silver-green PX-10 Peugeot racing bike to my dad. And I was given it for Christmas.

I couldn’t quite believe that I owned something so sleek and sporty. But it wasn’t just the exhilaration of speeding down the country lanes at the back of our estate near Croydon that unleashed the happy hormones. I was also instantly in thrall to the aesthetics of cycling: the time-perfected geometry of the bike frame; the way sunlight glinted on a polished hub; the purr of firmly pumped tyres on fresh tarmac; the satisfying ker-click of a perfectly executed gear change.

Very quickly I realised something profound had happened. I had become a cyclist. I belonged. But in a way that I now realise is characteristic of me, it was a loose, unbound type of belonging. Because apart from a few cycling holidays with friends, my cycling has always been largely a solo activity. Nonetheless, in 1971, I did feel part of a welcoming, mild-mannered fraternity. Cycling was different then.

Part of the appeal of cycling was that it was a way for me to express my embryonic environmentalism. A bicycle embodied progressive values and ‘pedal power’ was a way to challenge the dominant car culture, which I was pretty sure I was against. There was something else going on too. I hesitate to call it spiritual, but maybe transcendent is an apt description of the experience I felt on my bike when ‘everything came together’. So far, so Zen.

In 1976 my Peugeot went with me to art school in Corsham, near Bath. I used it every day to get to my studio from halls. It tranported me to country pubs, the local supermarket and to the digs of out-of-the-way student friends. Even at this early stage of my cycling life I used my bike mainly for getting from A to B.

In 1979 I moved back to Croydon, and then to various allegedly ‘up and coming’ parts of South London. First my Peguot was stolen. Then my Pearson. Then my Claude Butler. Each of which was a replacement for the former. Cycling was becoming less Zen, and I do think I questioned the wisdom of offering up yet another bicycle sacrifice. But I went ahead anyway and bought a Raleigh Rapide from Geoffrey Butler (RIP) in Croydon. I rode it each day from Battersea (home) to Croydon (work) and back during the mid 80s. On most days this was far from spiritual, but I still loved the sense of independence it gave me. And the residual art student in me, still with a hankering to be marked out as ‘alternative’, enjoyed the fact that my work colleagues thought it odd for a grown adult to actually choose to cycle to work when trains, cars and buses were all available.

When we moved to Kent in the 1990s a bike commute wasn’t an option. We did do a bit of exploring locally on our bikes when we first moved, but gradually it became more of an occasional thing. For the first time, my cycling became something done for its own sake (as in ‘going for a ride’, as in a short, medium or long ride). And between rides my Raleigh Rapide spent more and more time in the shed.

And that’s the way it was, with cycling and me, for a good decade or so.

And then I bought a Brompton folding bike. It was revelatory, a cycling reset moment. For a small wheeled bike the Brompton ride is really very good. But it’s the practicality and convenience that changes everything. The Brompton’s compact form when folded (folding and unfolding a Brompton tales about 15 seconds with practice) means it can be stowed away in small spaces, taken on a train, or flung in the boot of a car. Mine sits in our hallway, tucked behind the front door. Crucially, it isn’t in a shed or garage – I literally have to walk past it to leave the house. As a consequence of all these things I use it pretty much every day. Quite often two or three times a day. I use it for shopping, nipping around town, visiting my mum, going out for coffee – I might add in a couple of decent hills to make it feel a bit more like exercise. I get around town at about three times walking speed, which at certain times of day is slightly better than average car speed. I can park the bike securely – for free – just about anywhere, something made easier by the Brompton flip-wheel parking mode (we’re very nearly at the end of the Brompton talk). So, why wouldn’t I choose riding my bike over walking or using the car?

Despite what I think of as the ordinariness of my daily cycling, I get the impression it is considered by neighbours and friends to be slightly eccentric, borderline odd. Adults who use their bikes as their primary transport – researchers call us ‘resolute cyclists’ – are still statistical (and possibly societal) outliers. Which makes me think back to my dad’s friend and the decision he made back in 1971 to sell his bike when he returned home from Holland. If he could be transported to 2023 in similar circumstances, would he do the same thing? I suspect he might. In the Netherlands today there are 23 million bicycles – 5 million more than there are Dutch citizens. Almost every adult cycles. It is considered normal, and not – as it often is here – something that is regressive, or a provocation (just say the words ‘cycle lane’ out loud in any public forum to test my hypothesis).

When a team of Italian psychologists investigated the behaviours of cyclists across Europe they segmented them into ‘practical cyclists’ and ‘green cyclists’. I feel I have a foot (pedal?) in both camps. Similarly, I seem to have both ‘hedonic’ (referring to the “positive emotions experienced while cycling such as excitement, pleasure, and control”) and ‘instrumental’ (referring to the utility or functionality of cycling) attitudes to cycling.

Fascinating though A cluster analysis of cyclists in Europe: common patterns, behaviours, and attitudes1 is (honestly), academic compartmentalism of cycling behaviours feels slightly reductionist to this cyclist. It’s not that the pleasures of cycling defy analysis, it’s just when I get on my bike I never think about being an active part of a mobility culture or about the “elasticities of cycling behaviour”2. I’m just along for the ride. And if that sounds at all perfunctory, never underestimate the unconstrained pleasure of bicycle aided self-propulsion.

- A cluster analysis of cyclists in Europe: common patterns, behaviours, and attitudes, Fabrioni et al, 2021

- It’s the mobility culture, stupid! Winter conditions strongly reduce bicycle usage in German cities, but not in Dutch ones, Ansgar Hudde, 2022

2023

My Journey to jet Zero

My journey to Jet Zero (taking no flights at all that is, not the Government’s net-zero aviation strategy with its doubtful promise of ‘guilt-free’ flying) has been a long and slightly improbable one.

For the first 22 years of my life I didn’t take a single flight. This was mainly the result of my family’s unswerving devotion to camping holidays. In France. The rest of Europe might as well have not have existed as far we were concerned. A concomitant love of ferries and short sea crossings sealed the deal. The perfect holiday for us began with the sight of Portsmouth or Newhaven receding into the distance, with sea air and diesel fumes mingling in our nostrils.

Released from family holidays aged about 15, ferry ports continued to be the starting point for several subsequent summer excursions, with either bicycles or trains taking over in St Malo, Dieppe or Calais. The two trips I made to Paris in my late teens – one with my art school, the other as solo, fledgling flaneur – both involved SNCF’s characteristically low-speed rail network. Airports still weren’t on my radar.

But in 1981 I got a job in publishing and flying quickly became a regular feature of my new life as an environmental journalist (the irony of which can only be retrospectively appreciated). I took my first ever flight just a matter of weeks after joining the company, a “short hop” from Gatwick to Edinburgh my colleagues assured me. The experience was one of an hour and a quarter of alternating high anxiety (why is it making that noise, and, God, now this one?) and rapture (early evening sun bursting through diaphanous cloud cover as I drained the last of a tiny bottle of Dan Air Beaujolais).

For the next 30 years or so I flew on average about two or three times a year. For work (this detail is significant). This was mostly to attend trade shows or press conferences. Frankfurt, Hamburg, Hannover, Amsterdam, Nuremberg, Paris, Brussels, Malmö and Düsseldorf beckoned regularly. Atlanta, Tallinn, Hong Kong, Gaborone, Singapore, Beijing, Marrakesh and Boston just the once.

And as time went by my awareness of the climate impact of all these flights began to build as steadily as my accruing air miles. A chance meeting in the mid 2000s with Craig Sams, the founder of ethical chocolate brand Green & Black’s, at the Biofach trade show (the world’s biggest organic business event) might have been a kairotic moment. Craig told me that he had travelled to Nuremberg by train because he wanted to cut down on his flying. This was mainly to reduce his carbon footprint, but also a small act of defiance against the prevailing speed ethic (do things faster, get more done). Already an advocate for the Slow Food movement, Craig was now making the case for slow travel. Reassuringly, it took him near enough two days to travel from London to Nuremberg. Fine by Craig. But negotiating this extra travel time with my boss (more or less, allow a whole two days to get to the farther reaches of anywhere in Europe) and cost (travelling by Eurostar and Deutsche Bahn to Nuremberg was way more expensive than a budget air ticket ) would have been quite an ask.

So I carried on flying for work at roughly the same frequency for pretty much the next 15 years. By this time a high proportion of those press conferences and professional gatherings I was reporting from were actually about the climate crisis. My flying was now flying directly in the face of climate science. Yet almost no one in my agroecolgical peer group was talking about stopping, or cutting down, on their own flying.

Then Covid happened. And, for a short period, virtually nobody at all was flying. In March 2020 I became one of the legion of office workers suddenly working from home. That became an unexpectedly permanent situation when, in September of that same year, I was made redundant – in the process, unceremoniously grounded.

I watched with interest as the world slowly, but very determinedly, resumed flying. By March 2023, global air travel was close to 90% of pre—pandemic levels, while domestic flights in the US had reached 98.9% of 2019 figures.

I am both not surprised and surprised by this. Not surprised because flying regularly again is a signifier of things ‘getting back to normal’, a powerful and understandable impulse. Surprised, because awareness of the climate case for flying less soared in the early stages of the pandemic. Multiple surveys pointed to a heightened environmental awareness during that extended period of reflection granted us by the ‘great pause’. Many of us declared a new willingness to make personal sacrifices to combat climate breakdown.

But if flying less was part of those sustainable behaviours the commitment evaporated into thin air every bit as quickly as the hope that, post-pandemic, we might emerge a kinder and more compassionate society.

For most people, flying less is a behavioural change too far. That said, our resistance to any meaningful behavioural change seems pretty dogged at the personal level. As a letter writer to The Guardian (one D. Scott McDougall from Boise, Idaho) pointed out recently, it isn’t just the 1% or 2% of people who dictate the conversation and policies around climate breakdown who are the problem, it’s the “25-40% of people in the developed world who recognise the issues and impending outcomes, but go along with the status quo in order not to take a short-term hit to consumption standards.” And it’s true, our collective response to the fast-shrinking opportunity to save a habitable planet is a kind of studied ambivalence – for which the price we pay is to live in a state of permanent cognitive dissonance.

But why do we find flying in particular such a difficult habit to break? I’ll risk making a hackneyed observation: Flying regularly and conspicuously is a status signaller. To say “I’m in Madrid on Monday and Copenhagen on Thursday, how does Wednesday look to you?” is to remind someone about your importance. Unhelpful stereotyping? Maybe. But I find it difficult not believe that this is part of the psychological mindset that needs to be dismantled. Flying is also a behavioural addiction, as reported by a team of British researchers over a decade ago, and expanded on in their paper Binge flying: Behavioural addiction and climate change. The study highlighted the strategies of guilt suppression and denial that ‘binge flyers’ adopt in the face of a growing negative discourse towards air travel.

It’s rare to find environment industry professionals discussing in a public forum the question of whether they – we – should be flying less (or at all). When we do there is usually a vague consensus about quality over quantity (we should limit our flying to high quality, or the most important, conferences or trade shows). There’s sometimes more than a suggestion that what we do as a group makes such an important contribution to climate knowledge and mitigation action that there is a net climate benefit to our particular type of flying. I’m not so confident that we should pleading this sort of ‘special caseism’, or deploying a ‘deeper knowledge defence’ of our own habits.

Of course, as a group we’re up on the stats about the climate impacts of flying, and more likely quote them (the more flying-friendly ones that is). We’ll know that aviation is responsible for somewhere between 3-5% of global heating (when non-CO2 climate system impacts are accounted for) – a relatively small contribution compared to energy generation, manufacturing, agriculture and transport as a whole. But since we are also quite likely to be frequent flyers (defined as taking upwards of three flights a year), we’ll likely be in the 15% of people in the UK who take 70% of all flights. That means flying is likely to make up a significant slice of our personal carbon footprint – simply because, mile for mile, flying is the most damaging way to travel for the climate. For some context, a return flight from London to San Francisco emits around 5.5 tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) per person – more than twice the emissions produced by a family car in a year, and about half of the average carbon footprint of someone living in Britain*. Short-haul flights produce even higher CO2e emissions. A return flight from London to Berlin, for example, emits around 0.6 tonnes CO2e – three times the emissions saved from a year of recycling.

I’ve been putting off writing about this subject for a long time. Why? Probably for the same reason that if someone asks ‘aren’t you going away this year?’ (UK breaks don’t seem to count as ‘away’ ), I don’t ever reply: “No. I’m not flying any more to help stop planetary systems reaching tipping points that would trigger runaway climate breakdown, synchronised crop failures, mass starvation and displacement, societal collapse and human extinction”. I intuit that my barber doesn’t need to hear this. And, if I’m honest, I probably don’t want to come across as any more pious or judgemental to family and friends than I already do.

Actually, I can live with pious. Judgemental is more the issue, not least because I have friends who fly occasionally but whose otherwise low-carbon lifestyles mean they leave a smallish footprint.

But the campaign group Flight Free UK, which encourages people to take a year off flying, says the best thing I can do help change societal attitudes to aviation is to tell people that I’m no longer flying (and why). We do need to say this stuff out loud – to friends, colleagues, family – if we want to challenge the norm when it comes to flying and “shift the narrative away from taking flights as the default”. As an act of participatory solution seeking, this also brings benefits at a personal level by freeing us from eco-paralysis and its associated anxiety and depression. I’ll report back on how this all goes.

Before writing this, I made a list of all of the flights I’ve ever taken for holidays and leisure. Here they are:

1985 – Paris (our honeymoon)

2003 – Edinburgh (holiday with the kids)

2013 – Venice (30th wedding anniversary

2014 – Spain (daughter’s wedding)

2017 – Denmark (visiting old friends)

Seeing this written down makes me realise that I’m more of a freakish outlier than I thought.

Of course I’ve no idea how much my horizons would have been narrowed, how diminished I would now be, had I not done all that flying for work and witnessed the respective glories of Gothenburg, Clermont-Ferrand and Aberdeen at first hand. But, generally speaking, I don’t feel experientially deprived by my comically meagre flying record.

A lifelong lack of wanderlust and a visceral loathing of airports certainly makes it easier for me to pledge that I will now only fly very occasionally. But the main reason, I’d like to reiterate, is climate breakdown. According to Imperial College, ‘cutting back on flying’ is the third most effective thing ordinary citizens can do about climate change, after ‘eating less meat and dairy’ and – at number one – ‘making your voice heard’.

2023

Tate trodden

I have just spent two hours and fifty minutes walking in and around Tate Modern on London’s Bankside. I didn’t plan that specific duration but there was a temporal dimension to my visit since its primary purpose was killing time. And because technically I wasn’t actually visiting Tate Modern, just occupying its space (more on that later) and facilities, the experience was a different one. The whole approach was different.

I am never not impressed with the brute ugliness of Giles Gilbert Scott’s building, although this is a good deal harder to appreciate than it was before the Borough area of Southwark was ‘regenerated’ and colonised by foodies and brand agencies. Cultural cleansing has expunged all but the very last traces of Borough’s darker DNA.

In the very early 1980s I rented a small studio opposite Borough Market, just a few rotten cabbage strewn streets away from where Tate Modern now stands. Then you had to pick your way along truly sinister blackened streets lined with empty warehouses and redundant wharves to reach the Thames waterfront. Rusting winches swung cinematically in the wind on silent Sunday mornings (I often slept on the floor in my room at 1 Cathedral Street on Saturday nights and when I remake this walk in my head it is always on a bitter, leaden Sunday morning). The grime of centuries filled every pore of decaying brick and collected like tiny black snow drifts in the darkest recesses – a fossil record of London Filth.

When you did reach the waterfront you were corralled along narrow walkways, bordered by the grey-brown Thames. You would pass the Anchor pub – a nest of snugs and passages that in mid winter were often Marie Celeste-like in their absence of both drinkers and bar staff – and finally hit upon the little straddle of Jacobean houses at Bankside.

And then you were right under it, Gilbert Scott’s vertiginous monster. Brian Sewell once called Bankside Power Station Britain’s best example of fascist architecture. And on a monochrome winter morning in London you got the full fascistic effect – Albert Speer channeled through the aberration of British modern abstract classicism.

Today I approached Tate Modern across a small desert of gravel fringed with little architect’s drawing silver birches, the perfect foliage bearer for the white-out aesthetic of the contemporary art space. The Millennium Bridge that connects the north and south banks of the Thames lands just behind and funnels a stream of random humanity into a joyless example of late 20th Century hard landscaping.

Any pre-80s residual fear factor is dissipated by the hubbub of tourists, ice cream sellers, three-card-trick pliers, gallery goers and skinny jeaned chin strokers. Not that anyone seems to be taking very much notice of the brick colossus in front of them. That’s because when people rhapsodize over Tate Modern – and I mean the building, not the collection (which barely anyone at all mentions) – they are invariably talking about the interior space. It is the absence of anything at the very heart of this most venerated example of secular British architecture that people are really in thrall to; the hollowed out, now hallowed, space of the Turbine Hall.

“One of the most iconic urban spaces in the world,” the Tate website declares. And it does makes you draw breath when you walk into that cathedral-like space for the first time. How often does anyone encounter space in the raw like this? 120,000 cubic metres of central London real estate left shamelessly empty for months at a time. More than that, in its grey, weirdly granular light the thrilling void of the Turbine Hall succeeds as a liminal space. The ghost of heavy industry is inevitably invoked but so is the question ‘what next?’

Industrial metaphors abound when Tate Modern is discussed (unavoidably it is a “power house of contemporary art”). But the re-purposing of industrial buildings was already an art world cliché by the time Nicolas Serota was eyeing up Bankside Power Station as a potential second London base for the Tate. Whether power station, warehouse (Arnolfini, Tate Liverpool), train station (Musée d’Orsay) or flour mill (Baltic) gallerists love an industrial space. And when authentically industrial buildings are thin on the ground, former commercial sites – milk deport (The Dairy), 70s offices (White Cube Bernondsey) are commandeered.

Perhaps there’s the hope that an art gallery’s former industrial incarnation will confer some sense of purpose on its now ostensibly useless contents. I like to imagine a parallel with my early decision at art school to acquire, and wear at all times (including with gritty determination vists to the local Somerfield), a boiler suit. The boiler suit was the uniform of choice of the determinedly serious painter or sculptor: first task, get it filthy dirty (the thing came out of its polythene bag Ariel white making its wearer feel less industrial and more effete than ever). To deconstruct, I can now only think that this was more to do with cultivating an industrial aesthetic than about identifying with one’s fellow workers – who anyway would have fallen about laughing. It was a prop. One on which the art world still leans lazily.

So, while some would have liked a freshly minted iconic urban space – in the way that Bilbao got its Guggenheim, Paris its Pompidou Centre – London got in your face industrial space.

By one important measure – making the most of what it doesn’t have – Tate Modern is an unqualified success. And what a lot of people agree is that Tate Modern doesn’t have is an especially distinguished permanent collection – supposedly the reason for the ‘thematic’ hanging (why Monet and Matisse must jostle with Barnett Newman and Anish Kapoor on some fairly elastic art historical pretext). Although this is plainly what it is – a way of diverting attention away from some notable gaps in the Tate collection (for which my namesake J.B. Manson, the Tate’s famously modern art-hating director of 1930-38, must bear considerable responsibility) – walking through the galleries today you have to be impressed by how Tate Modern brilliantly anticipated the non-linear way the entire world would soon be curated by the Internet. Tate Modern is emphatically an art gallery for our times and it excels at a kind of casual connectivity.

Ralph Ruggoff, director of the Hayward Gallery, recently likened Tate Modern to the Bluewater shopping centre. Ruggoff was ostensibly commenting on issues of scale but I wonder if Tate Modern’s user experience was more front of mind. Brand conscious and instinctively mercantile – currently you enter via the gift shop (before being greeted by Tate membership agents and then passing through every level of cafe, bar and restaurant) – Tate Modern is the mirror of the contemporary retail experience: It encourages browsing – in this case of art; boutique shops and coffee stations pop up like store concessions as you follow your IKEA-like trajectory through the gallery; escalators disgorge visitors at Poetry and Dreams and Energy and Process as they might to Home Furnishings or Housewares. In this way Tate Modern has created a cultural cross-over zone, a reassuring familiarity that removes old obstacles to gallery going (never underestimate the art show’s potential as a theatre of embarrassments).

Waiting for my daughter and her friend at the main entrance to Tate Modern, I watched the art world segue almost perfectly with the normal world (near enough five million people flow in and out of this building over the year). Then on the mezzanine platform in the turbine hall, looking down on the human trajectories, orbits and eddies forming and unforming on the grey expanse of the floor below it seemed to me that it is as a human intersection that Tate Modern is most arresting: the art gallery re-imagined as a social medium.

2013

Habitat, Shabitat

You grow out of Habitat by the time you’re 40, a complete stranger once told me with a surprising air of confidence.

Looking around our house, a suburban monument to Habitat furniture of the period 1985-2000, I think she was probably right. We’ve bought a few frames and mugs since then but our last big purchase was the solid slate table that has sat utterly immovable in our dining room for 14 years. “Hope your husband’s strong,” one of the three knackered looking deliverymen who heaved the thing into the house apparently said as he sat slumped on a chocolate brown Habitat sofa (also late 1990s vintage), sugary tea in hand.

In the downstairs hallway a Habitat bedside cabinet has been repurposed as a telephone table. Upstairs a deconstructed 1980s Habitat wardrobe lies under a spectacularly creaky 1990s dark pine Habitat bed — and 15 years of human detritus. The last remaining side plate from a classic 1980s Scraffito Bistro Set languishes in a kitchen cupboard. In the bathroom one of our relatively few recent Habitat purchases, a wooden towel rail, regularly falls off the wall thanks to its bold, uncompromising design.

Our once hardcore Habitat addiction was finally defeated by the closure of the Tunbridge Wells branch. We would now have to travel 40 miles to Brighton or Canterbury to play the game of matching shelf prices with unticketed products, or marvel at the sheer gall of Habitat ‘sale’ pricing.

But our Habitat habit had been on the wane for a little while by then; thinking about it, since around the time we both hit 40. Perhaps we were growing out of it but the process was surely hastened by the idiosyncracies of Habitat customer service. For not only did Habitat introduce clean, contemporary design to the British High Street it also gave us our first taste of the air-of-studied-indifference class of store assistant.

Now, I think I’m pretty scrupulous about affording all my fellow human beings the same level of basic respect. I don’t look down my nose, or up my nose, at anyone. I’ve never equated service with servitude when I’ve worked in shops myself. So to begin with, being fastidiously ignored by immaculately turned out Habitat staff was a source of fascination more than anything.

Generally you’re not in a hurry when you’re shopping in Habitat — nobody dashes in to buy a Pineapple Tea Light Holder or Chicken Brick. But when you’ve been standing by the cash desk with your Chicken Brick for 20 minutes while two Habitat sales assistants hold a meeting in the furniture department and another taps away insouciantly on a laptop your own reserves of insouciance quickly evaporate.

If I’m sounding bitchy about Habitat it’s probably just that perennial impulse to hurt the one you love. And it’s been a long affair, my relationship with Habitat, going back in time a whole lot further than the 1980s. I vaguely recollect visiting one or two of the 1960s stores. Although no more than impressions — glimpsed through the Super 8 filter of the mind; grainy and soundless — these are firmly implanted in childhood memory. Thus they are part of the chemical architecture of grown-up, middle-aged me.

I’m not sure my mum and dad actually bought anything from Habitat in the 1960s. They probably just went to look around the place — looking, not spending, being a characteristic feature of Manson family days out (‘Manson family’ never looks good in print). In any case they probably would have viewed the Habitat inventory of the time more as mildly comedic than youthful or aspirational.

It was in the late 1970s that I discovered Habitat for myself. I was working as a junior reporter in Croydon and Habitat, though it was entombed deep in the Whitgift Shopping Centre (Nicolas Ceausecu’s long-lost shopping mall project?), provided the closest thing to a lunchtime retreat that Croydon could offer. This quarry-tiled oasis of calm was where I first consciously became aware of the pleasures of Storage. Its cafe was where I had my introductory exposure to croutons — and did my first ostentatiously intellectual reading.

Thinking about this ought to make the final demise of Habitat seem sadder than it does, more personal. But it’s just funny. Despite now resembling the Pound Shop, in the dying days of its closing down sale the Brighton branch is still only offering 30% off on the random mugs, toilet-roll holders and lone dining room chairs left scattered around the shop floor.

Well at least Habitat’s sense of humour is intact, even if the business model fell apart years ago.

Habitat may be gone but in Brighton we still have Shabitat. At ‘the people’s Habitat’ you can pick up an armchair for a fiver or a chest of drawers for tenner. A Chicken Brick ought to set you back about 50p.

2011

Here comes there sunset

Yesterday evening I encountered an affecting modern day act of communion on Brighton Beach.

At least that’s what I’m telling myself it was.

Like hundreds of other people, I had been drawn through darkening streets towards a fiery orange effulgence. Down on the beach we stood alone or gathered in small groups to watch a mesmerising sunset, framed rather obligingly by the rusting armature of the West Pier.

It felt good, being part of this act of mass gratitude for an unexpected gift of late summer warmth.

Then I noticed the cameras and the phones held aloft and pointed westwards. Almost everyone was photographing the sunset, not seeing the sunset. And I wondered if what I was witnessing was actually a collective failure of the primary experience, to use Michael Foley’s phrase, rather than a poignant coming together of day-trippers, office workers and conference delegates.

So I scrunched back up the shingle, slightly despairing that a primordial human experience had been reduced to a photo opportunity.

But as I watched the scene in front of me, the cameras and smartphones glinting in the late afternoon sunlight, I was aware of a palpable sense of fellowship right there on Brighton beach. We had gathered in a sort of digital communion.

Yet I still wasn’t entirely sure I wanted to advertise my own complicity in all of this. So I slipped my Canon G10 into my jacket pocket, picked up my backpack and walked off into the real sunset.

2010

MOLESKINE DILEMMA

Yesterday I overheard a middle aged man lamenting to a friend why something or other was so “excruciatingly middle class”. He did this whilst: 1. Sipping an espresso macchiato in Carluccio’s. 2. Ostentatiously making notes in his Moleskine notepad.

Yes, that’s right, two utterly middle class affectations indulged simultaneously without the slightest sense of irony. Funny really.

None of which is my immediate concern. I’m a Moleskine user too. Or, more accurately, I’m a Moleskine hoarder. I like them like everyone else because they look purposeful, artistic and handsome.

Two things trouble me though.

One is the Moleskine Effect. For anyone over 25, seeking this is surely pathetic. The idea (I imagine, since every Moleskine comes with a little leaflet listing the various literary and artistic gods who have ‘carried’ one), is that when you casually slip a Moleskine from your battered satchel and ponder it thoughtfully over an espresso, your fellow coffee sippers will imagine you’re a latter-day Chatwin or Hemingway.

Second is the difficulty I seem to have in actually using a Moleskine. I buy a normal notepad or sketchbook; I start scribbling away. But the Moleskine sits there with its lovely wrapper and explanatory leaflet (Classic Hard Cover, built-in elastic closure, cloth ribbon placeholder, expandable accordion pocket for holding tickets, notes and clippings) demanding that you fill its first page with something much more profound than ‘Things to get at Homebase’, or a five minute sketch of next door’s conservatory (done at a recent low point of artistic stimulus). It calls out for something Chatwin- or Picasso-esque.

Hence the growing pile of pristine Classics, Volants and Cahiers.

When I do self-consciously get a Moleskine underway the jottings peter out a few pages in. I know I’m going to have persevere, not least because there is a considerable investment tied up in these unused Moleskines (Father’s Day, Christmas and birthdays will bring more).

So the other morning I went out into the garden and told myself “to hell if I write something trite or ruin my new Moleskin with a crap drawing”. I sat down on our bench and drew next door’s conservatory and our lap-larch fence. It was crap and I knew it. I picked up my latest Moleskine and went back inside feeling just that bit more more artistically defeated.

2010

Strategy day sunset

I’m not sure if retroactive blogging really is in the spirit of the thing. But looking at this photograph again, and remembering the mildly surprising circumstances of its making, prompts a post-dated observation.

It’s late afternoon in early February. We’ve spent the day in the top floor Conference Suite at the Hotel Metropole Brighton.

The strategy day is over. The flip chart pages have been torn off and the marker pens collected up. A solitary bourbon remains on the once abundant biscuit plate.

I walk over to the floor-to-ceiling glass doors and slide them open an inch or two. Cold sea air sluices into the room and hits four star fug. I step out onto the balcony and slide the door behind me.

Inside, the team are folding their course notes into handbags and backpacks and debating the merits of a wind-down beer in the bar. Outside, a phantasmagoric vision is forming over the English Channel. It’s invisible to everyone in the room, who just see the garishly lit conference suite reflected back at them.

Click. I have my strategy day sunset.

2010

SIT BACK AND ENJIY THE ABSURDITY

I’ve just this minute finished Michale Foley’s book The Age of Absurdity, which, among many other things, invites us to look upon absurdity as the new sublime.

While they are fresh in my mind I thought I’d just remember out loud a few favourite Foleyisms.

Happy, shiny work people

Foley notes how employees increasingly have to present and develop themselves not as a person but as a brand. And the brand identity? “Bubbly and smiley”. God help you if you don’t want to “lighten up and have fun”.

Hard wired for fatalism?

Foley references some impressive neuroscience to challenge the pervasive concept of the ‘hard-wired brain’. “Far from being fixed millions of years ago the individual brain constantly rewires itself throughout a lifetime in response to experience,” says Foley. This newly discovered plasticity allows the creation of entirely new brain configurations through persistent, attentive activity of more or less any kind. It also renders less useful the excuse “I’m an arsehole because I was hardwired to be an arsehole. It’s just the way I am”. Your basic temperament may indeed be set at arsehole, but if you really work at it you have the potential to be just mildly irritating.

Staying cool is such hard work

Foley: “…staying cool is hard work because the cool is constantly destroyed by mass adoption. It was cool to get a tattoo when tattoos were the insignia of the dangerous outlaw — but soon even suburban housewives had tattoos on their bum”. Unarguable.

Real-life just seems boring these days

Giant-size, miniature, plasma, touch — the screen is omnipresent. Pin sharp, bright, highly edited — it’s making real-life seem boring. The increasingly frenetic rate of image change of our new screen lives is also putting our brains into a continuous state of psychological red alert. Brain and body simply can’t recover equilibrium.

Foley shows that this growing addiction to passive, stimulus-driven entertainment means we struggle with anything static and slow moving. We’re losing the capacity to concentrate. Read a book? Have a conversation? Focus on a single task? Forget it.

The failure of the primary experience

If it wasn’t photographed, or it didn’t get videod, it never really happened. We live our lives through a lens, and then view it on our “shiny, twit machines” (thank you, Charlie Brooker, for that one)

Micro evolution — adapting for the workplace

To a greater or lesser extent we are all actors when we’re at work. Foley laments that we become a “simplified persona” — shallower, actorish versions of our true selves — through a process of unconscious adaptions. These generally take mildly depressing forms. For example, Foley drinks cheap instant coffee at work and it’s always tasted fine. At work. He knows if he drank it at home (where he always grinds beans to make fresh espresso) it would taste vile. At work, he concludes, “even my taste buds renounce complexity and depth”.

Where did my vibrancy go?

As well as the “ceaseless acting” we do at work, says Foley, we also channel considerable energy into maintaining that bubbly, smiley persona. This is bloody hard work and everyone needs a break. Hence when you spot colleagues out of work — in the lunch hour for example — they often appear “shabby, diminished and furtive”. They’ve gone “off the set” and the artificial vibrancy has been extinguished.

Lost the plot? There never was one.

Not infrequently I am reminded of my inability to follow a plot (of a film or book). This is viewed by my family as mildly comical or “a bit sad”. But I’ve always maintained I’m just not that interested in plots, or narratives generally. And now, in Michael Foley, I have discovered a fellow traveller.

The pleasure of the plot is all expectation and sensation, says Foley — but the “dénouement of the plot-driven novel is often implausible and disappointing, so the pleasure is illusory and short-lived”. Novels that reproduce some of the texture and feeling of life are less likely to rely on plotting — no need, real life has no plot — but are more likely to provide richer satisfactions and live longer in the mind. Says Foley. And says me.

Needless to say The Age of Absurdity is determinedly and joyfyully plotless. Foley ranges around his subject — contemporary cultural conditioning — with abandon. A contrarian on the loose, in the age of conformity as well as absurdity.

2010

Back from the Kentish edgelands

When I told people we were going on holiday to Whitstable I could detect a note of sympathy in every “oh, isn’t it meant to be really lovely?” Perhaps that’s because almost all of them were jetting off to Greece, Turkey or America (point of interest: the more environmentally concerned the friend, the more ruthlessly carbon-emitting the holiday).

Anyway, Whitstable is lovely. Lovely both in its differentness (which it plays on) and its almost touchingly old-fashioned ways. You really do you have the feeling sometimes that time stood still in about 1968.

It is true that Whitstable has become a favourite weekend destination for London foodies (give me strength) and you’ll see some painfully ostentatious displays of oyster and Champagne guzzling going on around the harbour on sunny weekends. Sometimes you’ll hear the locals comment on this. I overheard one elderly woman explaining to another elderly woman who (I’m guessing) had come to visit for the day “Oh yes Dorothy, it’s become very popular with people from London”. It wasn’t said in a judgmental way, more a reassuring explanation to Dorothy of why some of the people looked and behaved like they did. The one word — London — seemed to explain everything.

Walk a little way along the beach and the foodies and their hampers quickly thin out. It’s mostly families huddled against the wooden groynes, armed with windbreaks and travel rugs. You’ll see a few brave souls bobbing around in the sea — Thames Estuary, technically. Human shrieks mingling with the squawking of the gulls on brisk northerlies.

I like the place best late in the evening. The shingle beach, tufted with marram grass and red valerian, is virtually empty. To the north you can make out the Essex coast, to the east the turbine blades of the Kentish Flats Wind Farm luminesce in the moonlight. This is the time when Whitstable starts to exert its otherness. As with that other Kentish edgeland, Dungeness, there is the sense here of being just out of reach of everywhere else. The straggling line of beach huts is like a tiny frontier town, but one that marks the end rather than the beginning.

2009

Oh, what a carve up!

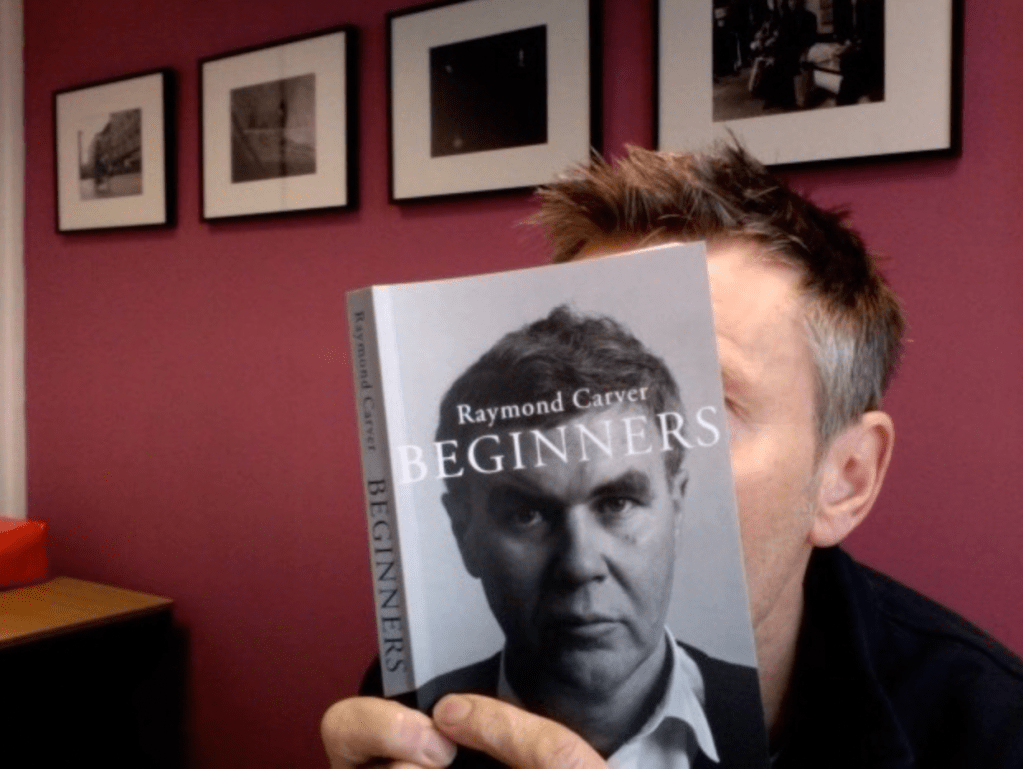

It’s probably 25 years ago or so that I first read Raymond Carver. I remember picking up a short story collection in a bookshop in 1980-something and being impressed by two things: the blurb on the back (topnotch authors and critics virtually falling over themselves to say how good these stories were); and the cover photograph of Carver looking just like the “best American short story writer of his generation” ought to look — all brooding intelligence and purposeful knitwear.

Another rather obvious case I’m afraid of me judging the book by its cover.

So anyway, when I first read What We Talk About When We Talk About Love I’m fairly sure I did so still strongly under the influence of superlatives (let’s put knitwear to one side). But even then the feeling crept up on me that maybe these stories were just a tiny bit unsatisfying. I began to wonder if it was Carver’s trade-mark writing style itself — the celebrated economy of language and pared down dialogue, the barely glimpsed at lives of his sad, blue-collar characters — that was leaving me feeling narratively short-changed.

Two other collections came along later — Cathedral, 1984, and Elephant, 1988. And with them came more high praise for that compressed and intense form, which by now had spawned a stream of imitators and gained a nomenclature: Carveresque.

In truth, I’m not sure I thought too much about Raymond Carver between the late 1980s and last weekend. But there in a double page spread in last Sunday’s Observer Magazine was that picture of Ray in his polo knit.

The four-page article, constructed largely around an interview with Carver’s second wife, Tess Gallagher, coincides with publication of ‘uncut’ versions of the author’s manuscripts. Gallagher, who has overseen the Carver estate since Ray’s death in 1984, wants to derail (or at least send off into the sidings) a reappraisal of Carver by literary critics which has him recast as a relatively minor writer made big by the brilliance of his editor, Gordon Lish.

Lish championed a whole stable of rising American authors — Carver, Barry Hannah, Amy Hermpel and Richard Ford among them — as literary editor of Esquire magazine and later at the book publisher Alfred A Kopf. In the process he acquired (or gave himself) the title Captain Literature.

As a reputation maker, Lish’s talent’s were — are — indisputable. Lured to his legendary writing workshops (likened by one alumnus to 1970s-style primal scream therapy) those fledgling novelists who survived being beaten to a critical pulp were scraped off the ground, refashioned and thrust into the literary limelight — many to become big name writers. Whether they, or their writing, were ever the same again is another matter. As Gerald Howard has noted, they were all guinea pigs in Lish’s mission to “sweep the well-made story into the dustbin of literary history”

Accusations of “slash and burn editing” were one thing. It was the creeping contention that Gordon Lish had effectively been Carver’s ghost-writer that really had to be dealt with. Hence publication now of Carver’s unedited manuscripts as a form of enforced stock-taking.

But letters recently made public show that Carver himself fought hard, if in vain, to prevent what he called the “surgical amputation” of his writing. Pleading with Lish to give his characters and stories some breathing space, he wrote: “Gordon, don’t leave these stories with limbs and heads of hair sticking out”.

Comparing the opening pages of Lish’s edit for What We Talk About When We Talk About Love with Carver’s original draft (titled Beginners) is instructive. Within the first paragraph Lish has renamed the central character (Herb becomes Mel, no explanation given) and deleted or severely truncated several sentences. Some stories in the collection are cut by 50 to 70 per cent.

But not only do the stories lose half their length, those renamed characters (Bea becomes Rae, Kate becomes Melody, Cynthia becomes Myrna) are blunter, more brutal presences. As Gaby Wood wrote in her Observer piece, Lish’s edits — made as if the editor “knew the writer’s inventions better than he did himself — alter the plots and characters way beyond issues of nuance and shading, they are close to being different stories altogether. Gordon Lish’s stories”.

I’ve just gone out to buy a copy of the new edition of Beginners. I want to read the fleshier versions of the stories cut back to the linguistic bone by Gordon Lish; find out what once filled the narrative silences and have Ray’s characters complete their sentences. Yup, I think I’m ready for pre-carve up Carver.

2009

TRAGIC IN TONBRIDGE

The other Saturday morning I popped into the Tonbridge branch of WH Smith to have a free read of their art and photography magazines.

I’ve noticed an interesting code of etiquette among the ranks of tight-fisted men (it is invariably men) who congregate around W H Smith’s magazine racks at the weekend. We murmur apologies if we encroach on each other’s personal space and execute a sort of blokey pas de deux, whilst still reading, to allow a fellow freeloader to pop back their finished with copy of Stuff or ArtWorld, or Total Carp. Believe me, you get all sorts.

Heading out via the book department I noticed a new section devoted entirely to Tragic Life Stories. It’s a ‘genre’ according to W H Smith’s, presumably in the same way that books by Top Gear presenters are a genre according to W H Smith’s. But the sheer number of TLS titles got me wondering whether Tonbridge was somehow a uniquely tragic place.

Later in the day, still troubled by this thought, I decided to test out my new tragic-o-meter on Tonbridge’s near neighbour, Tunbridge Wells. For God’s sake, the T. Wells branch of Smith’s has double the amount of shelf space devoted to books with titles like:

Mummy Doesn’t Love You

Cry Silent Tears

I Just Wanted to be Loved

Ugly

Behind Closed Doors

Destroyed

Fractured

Mummy Come Home

Forgotten

Nobody’s Child

A Child Called It

A Man Named Dave

No way home

Boy A

No One Wants You

The Burn Journals

I Just Wanted to be Loved

Searching for Daddy

Please Don’t Make Me Go

Don’t Tell Mummy

Ma Sold Me for a Cigarette

That’s a lot of book titles, I know, but you really have to seem them en masse to get the full miserable effect.

Well, my fledgling theory about Tonbridge is in tatters. It is tragic, but no more than anywhere else. The march of Misery Memoirs is unstoppable. They and Jeremy Clarkson deserve each other.

2009

May a plague of gratuitous optimism be upon you

‘Scientists find flaw in self-help philosophy’ ran a headline in The Times last Saturday. I can’t say I’m surprised — but then my congenitally sceptical outlook has been preparing me for this for a lifetime.

Psychologists in Canada have concluded that positive thinking is a dangerous tool in the wrong hands. Chanting mantras such as “I can do it” turns out to do more harm than good for people who can’t do it, and never have been able to do it. It’s fine for people who already have good self-esteem in the first place — they actually believe what they’re saying. Sadly, no amount of telling yourself “I’m a loveable person” is going to help if your starting point is self-loathing.

But my own dim view of self-help books isn’t just to do with my innate contrarianism, it’s also to do with my innate snobbishness. How do I know this? Because I have just been reading Alain de Botton on the subject.

Here is de Botton in The Times: “There is no more ridiculed literary genre than the self-help book. Admit that you regularly turn to such titles to help you cope with existence and you are liable to attract the scorn and suspicion of all who aspire to look well educated and well bred.”

Ouch, that’s me all right. Scornful as well as sceptical.

De Botton blames the lowly reputation of self-help books partly on the way they are packaged by publishers in “sickly pink and purple” jacket designs and then “entombed by booksellers near the mind, body and spirit section”. But he also identifies a more fundamental problem: self-help books these days are written by all the wrong people. Note ‘these days’.

De Botton reminds us that the history of the self-help book goes back to Ancient Greece. Epicurus wrote 300 of them with titles like On Love, On Justice and On Human Life. The Benedcitines and the Jesuits added to the canon, along with assorted philosophers down the centuries. Here are some 19th Century pearls of wisdom from Arthur Schopenhauer, who advised in 1823: “A man must swallow a toad every morning to be sure of not meeting with anything more disgusting in the day ahead.” (Later, at lunch with his publisher: “Arthur, we really must call this The Toad Less Travelled …”).

Sadly, says de Botton, after the 19th Century the self-help field was “abandoned to the many curious types who thrive in it today”. The problem is, he says, we need self-help books like never before.

The solution? Well, de Botton wants our “serious writers” to embrace the genre. Imagine, he says, what Emerson, Carlyle or Virginia Woolf could have done with it. Or Shakespeare (“Twenty tips from Othello on relationships”).

I suppose it depends on whether you want to receive life-advice from the likes of Will Self or Martin Amis. Personally, I’m sticking to my own life-long life-strategy: Keep your expectations about things and people low. That way you won’t end up disappointed.

And here, if I may be a little immodest, I detect some convergent thinking. De Botton’s big issue with contemporary self-help books is their gratuitous optimism. This is where modern practitioners “are utterly cut off from the spirit of their more noble predecessors”. The self-help gurus of the past knew that the best way to make someone feel well was to get them to accept that things were every bit as bad as they thought they were. And probably worse.