It’s the late 1950s and the American artist Philip Guston is at the pinnacle of his abstract expressionist phase. He should be enjoying his major player status as part of the exulted New York School. But Guston is struggling to find meaning and purpose in abstraction. Torn between competing impulses – depicting the actuality of the world around him, or abstracting it – he is hit with a juddering realisation: “The hell with it, I just want to draw solid stuff”.

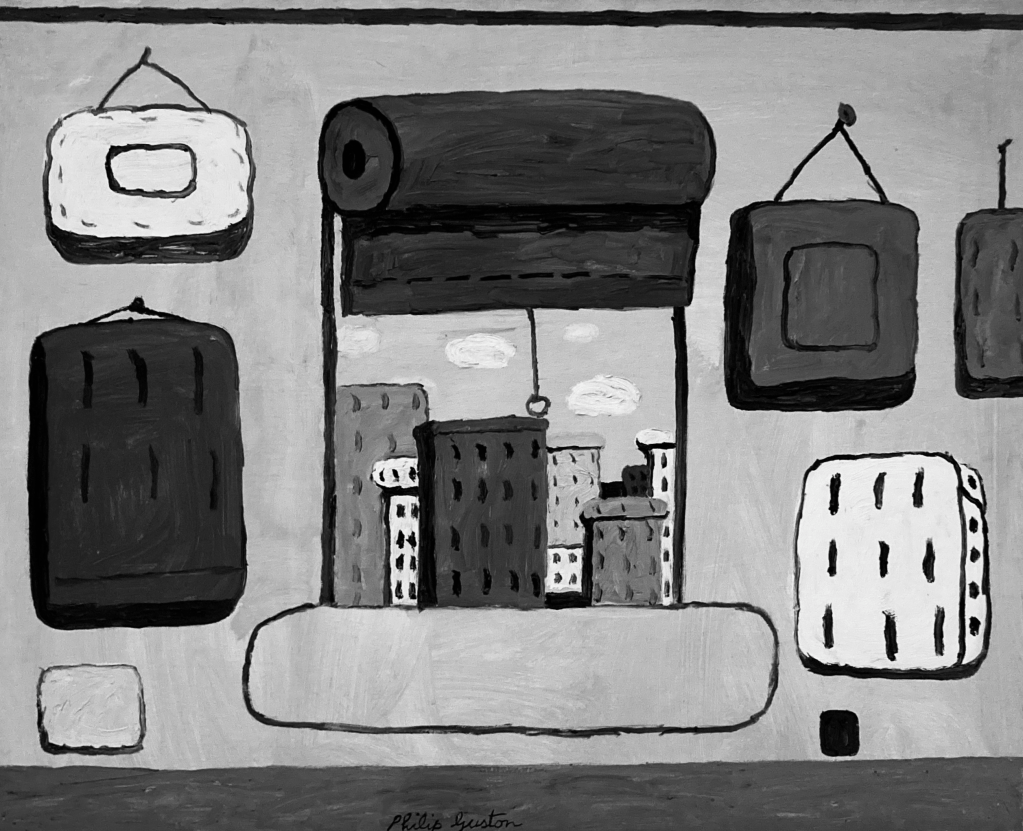

Guston was done with the loops and skeins, the diaphanous veilings of abstract expression. His abstract painting was boring him. To the extent that he stopped painting for an entire year. Then he began, slowly and deliberately, to draw his way back to painting. Over the following year, sparse arrangements of horizontal or vertical black lines and simple grids gradually morph into the heavy outlines of everyday objects – books, shoes, boxes, window frames. Figuration had come calling again.

Renouncing abstraction (Guston had decided that American abstract art was “a lie, a sham”) was one thing. But the way Guston effected it, as a kind of artistic handbrake turn, had instant reputational consequences. When he first showed the new work – including early versions of the ‘hoods’ (cartoonish paintings of Klu Klux Klan-like figures in unsettlingly banal situations) – at New York’s Marlborough Gallery, in 1970, the reaction was excoriating.

The provocative iconography of Guston’s figurative work has been the focus of most recent discussion about the artist. But in 1970, what Emma Sullivan has called Guston’s “violation of virtuosity”, caused just as much offence. Critics and artist friends alike were horrified at what they saw as the crudeness of Guston’s new cartoon-like idiom. As Guston recounted in an interview with Michael Blackwood: “They told me they hated the new work. One of them, and I don’t need to name names, said to me, ‘Phil, why did you have to go and do that?’.” Perplexed at Gaston’s apparently wilful embrace of ugliness John Cage could only say, “but you’re living in such a beautiful country”.

Several commentators have likened Guston’s dramatic return to figuration to Bob Dylan going electric at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. No one actually shouted “Judas” at Guston but purists in both spheres were riled in about equal measure.

In declaring himself “sick and tired of all that purity”, Guston was disassociating himself from what he saw as the introspective preoccupations of abstract expressionism. As Karen Schneider put it, “he felt that he could could no longer justify the luxury of adjusting a red to a blue in his abstract painting when the world was in turmoil”.

Artists falling out with artists is sometimes unavoidably funny. In the case of Guston’s bust up with the Abstract Expressionists, the comedy potential was in proportional relationship to the deadly seriousness of the endeavour. Guston had dared to challenge the heroic narrative of American Abstract Expressionism, cultivated so assiduously by artists, critics and gallerists alike. The bait was laid. The AbExers swallowed it whole.

Philip Guston is showing at Tate Modern until February 24.

2024

Leave a comment